CIRCLE and OYUnited: Improving Voter Access through Research-Fueled Action

by Adam Strong

Our ongoing partnership with Opportunity Youth United (OYUnited), a movement of current and former opportunity youth, has shown that there are many levers to increase young people’s access to voting. Many of these involve policy reform, while others can be pursued and accomplished by community actors. One key opportunity is building mutually beneficial relationships with local election administrators to improve access to voting for those who are often disadvantaged in civic life and participating in elections—particularly those who live in low-income communities and in black and brown communities.

We call this work Expanding the Electorate. During the first phase of this project, we partnered with OYUnited in participatory research focused on identifying possible barriers and challenges to young voters, particularly low-income youth. In our initial report, we outlined large inequalities in young people’s knowledge of essential information needed to vote (e.g., almost 2 in 5 youth surveyed did not know where to vote) as well as other structural challenges (e.g., 1 in 4 needed a ride to the polls) that impeded low-income youth’s ability to participate in elections. Based on these findings, we created 10 recommendations for how election administrators can work to increase voter engagement.

In order to advance this work, in 2019 we coordinated an initiative to give grants to three pilot sites—groups of community-based young leaders, in Seattle, Los Angeles, and Tucson—to join a learning cohort. Over the course of seven months, they identified barriers and challenges that may prevent young people in their communities from casting a ballot, and then pursued a partnership with their local election administrators (EAs) to systematically improve voter access in one specific, targeted way. Both our initial research and the subsequent success of our pilot sites were made possible by a grant from the Democracy Fund.

The work of young leaders in each site leveraged, highlighted, and expanded on key takeaways from our research. Some highlights:

- Young people and young organizers have information, networks, and experiences that can be helpful to local election administrators’ efforts to reach more people in their communities. Our Los Angeles pilot site expanded the capacity of its local election office by creating a platform for EAs to educate and disseminate information systematically across their network of youth serving organizations.

- Local election administrators often have many responsibilities and limited capacity to perform proactive outreach. Youth organizations can help by creating opportunities to hear from a wide diversity of youth about their experiences with elections and how youth are (or aren’t) finding election information. In Seattle, young people partnered with the King County Elections office to expand direct outreach and voter education and registration efforts to low-income and housing-insecure young people. They hosted six voter education and engagement listening circles across their county and led a social media campaign focused on dispelling common myths and false assumptions articulated during those listening circles.

- Direct communication and collaboration between election administrators and young people can increase youth knowledge and interest in elections and trust in local election officials. In Tucson, the young leaders had to learn about and navigate a complex local electoral administration system with multiple offices overseeing different functions. Eventually, their partnership developed mailers to educate youth about voter rights and to increase trust among young people who incorrectly thought that they were disenfranchised because of a lack of ID, a criminal record, or various other issues.

Supporting Young Leaders and Reducing Barriers to Voting

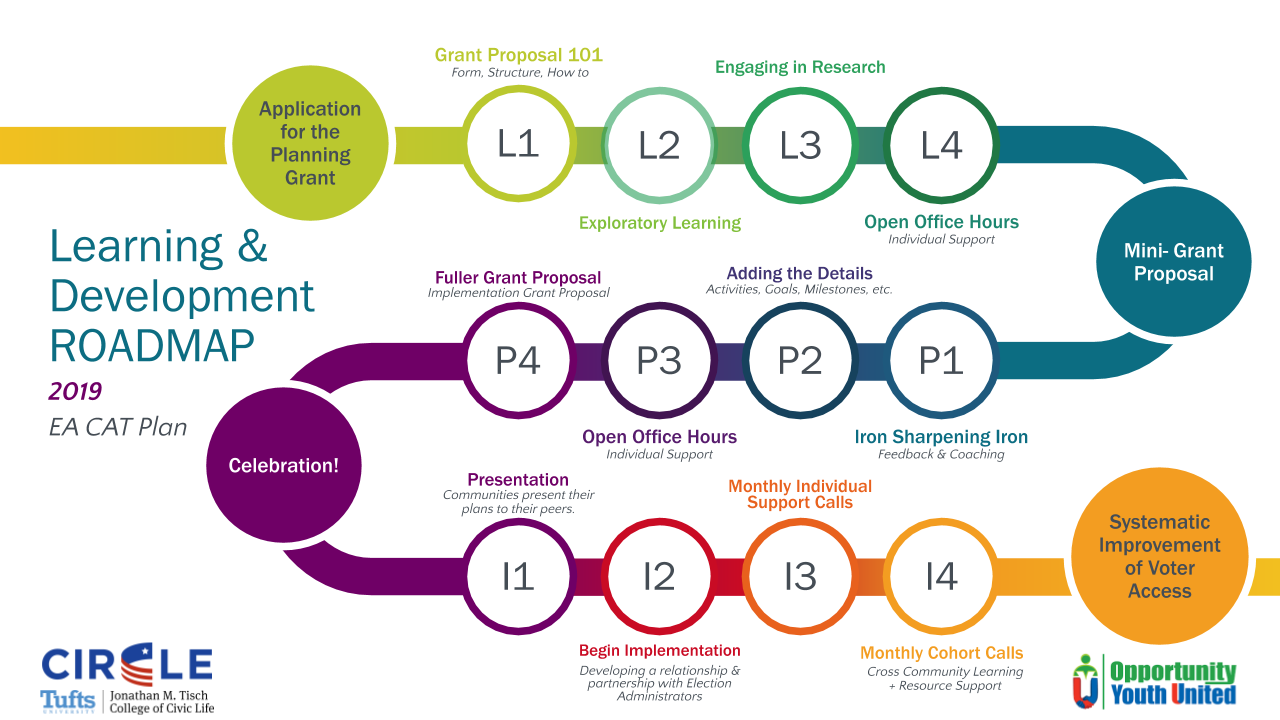

To establish our pilot sites, we partnered with three of OYUnited’s youth-led community action teams (CATs). The first stage involved the CATs exploring our research to build on their existing knowledge and experiences of barriers and challenges to participating in elections. The second stage focused on developing potential action plans for partnering with election administrators to improve voter access in one specific way. And the final stage involved implementing their plans, building those relationships, co-developing joint projects and initiatives with election administrators, and learning as a cohort across the three sites.

Developing the CAT members’ capacities as young leaders was a central component of this initiative. That involved learning about election administrators’ roles and elections work more broadly, finding and interpreting data, and grant-writing. We supported this development through monthly support calls and community learning sessions that included supplemental resources, talking points, partnership tips, and group problem-solving.

In designing the initiative, we recognized that time and funding is often a barrier for young leaders to participate in these and other civic opportunities, so we worked to ensure young people were compensated for their time. We split our project and application into two stages that would allow us to award a small grant to those who joined the initiative to research, craft, and write a proposal, and a second grant (if selected) for progressing to stage three and implementing their plans. We also encouraged grantees to include in their budgets compensation for the young leaders who participate and lead in their local initiatives. Above all else, we wanted to ensure the opportunities provided in each community were meaningful, transparent, and accessible.

Each pilot site’s approach to improving voter access in their community varied based on a multitude of factors. Below are short spotlights for each one:

Seattle, Washington

In Seattle, the community action team had an existing relationship with the King County Elections office, which was proactively seeking to improve voter outreach and education to opportunity youth in ways that the CAT was uniquely suited to support. They hosted voter education and engagement listening circles across Seattle’s re-engagement centers (locations serving opportunity youth to help them get their GED and connect them to employment opportunities) and youth homeless shelters. Leveraging the lessons learned from the listening circles, the youth-led CAT launched a social media campaign that used infographics addressing common myths and barriers to voting identified by young people. In this way, the Seattle CAT aimed to increase voter access for opportunity youth by providing essential information, addressing the transportation barriers and other challenges affecting youth, and increasing trust between election administrators and opportunity youth.

Los Angeles, California

In Los Angeles, the youth-led CAT was able to expand the capacity of their local election office by creating more connections for EAs to educate and disseminate information systematically across a network of youth serving organizations. They convened district-wide organizational stakeholders to streamline election conversations and education. The CAT’s young leaders wanted to address a perceived culture in which youth-serving organizations in their community did not communicate or engage enough with their local election administrators to ensure their young people had the information they needed to register to vote and cast a ballot. Given local changes to the voting process in Los Angeles, the young leaders thought it was essential to partner with their election office and expand its capacity. The CAT built a relationship with local election administrators from the ground up by attending mock elections and stakeholder meetings hosted by the election office.

Tucson, Arizona

In Tucson, the CAT partnered with their local County Recorder’s office to produce and share voter educational materials tailored for opportunity youth outlining critical information about voting. The young leaders had identified that many of their peers were unsure of their voting rights. This tracks a finding from our participatory research project with low-income young people, which highlighted that many had inaccurate information about who was disenfranchised and under what circumstances. For example, one in five (20%) youth we surveyed believed that if they were convicted of a misdemeanor they could not vote, and two in five (41%) were unsure if they could. In fact, they could vote, and the majority of states now allow those with a felony conviction to have their voting rights restored.

The CAT had no prior relationship with their local election office and administrators, and initially faced difficulties in establishing contact. They persisted, and by leveraging a contact in the Mayor’s office, they became aware that some election-related functions are administered by their county Recorder’s office and not the local election office. They reached out via email to that Recorder’s office and scheduled a meeting with administrators there who were enthusiastic to meet and collaborate with the young leaders.

Each pilot site faced and overcame a host of challenges related to their unique project aims, navigating multiple systems and stakeholders, and developing and nurturing their relationships and eventual partnerships with election administrators. All of the pilot sites plan to build on the successes they achieved during this grantee initiative with projects that include election administrators as they continue to pursue improving voter access in meaningful ways.

The work of our grantees also underscores other important issues that youth and organizations should keep in mind as they consider potential partnerships. Election administrators are often incredibly busy during election years, all of our pilot site teams noted that communication and outreach with EAs was difficult because of scheduling. Patience, persistence, and flexibility are essential to successful collaborations and partnerships. Additionally, it is important to recognize that some EAs may not initially be open to partnerships for a multitude of reasons: from being overworked to having prior negative experiences with other groups or organizations. Navigating relationships with your local election office may not be easy or possible in all situations; however, when it succeeds, a community’s young voters can reap the benefits.

Of course, for the 2020 election there is an additional complication: the COVID-19 pandemic. Election administrators, organizers, campaigns, and others around the country are beginning to grapple with what that will mean for the voting process and for the vital task of reaching out to young voters. This will certainly be a major challenge, but it can also be an opportunity that highlights the value and importance, now more than ever, of partnerships between EAs and youth.

Already some jurisdictions are considering or expanding opportunities for young people to serve as poll workers or take on other election-related roles (health and safety permitting) as we face the prospect of elections shaped by the pandemic.

In the coming weeks, we will continue to distill and share lessons learned from our pilot sites for practitioners and others looking to replicate their success by partnering with their local election administrators to expand and diversify the electorate. To learn more about local election administrators and officials, consider reading Stewards of Democracy, a report produced by the Democracy Fund that covers the 2018 survey results of more than 1,000 elections officials nationwide regarding their opinions about election administration, access, integrity, and reform.